The Pull of the Planets

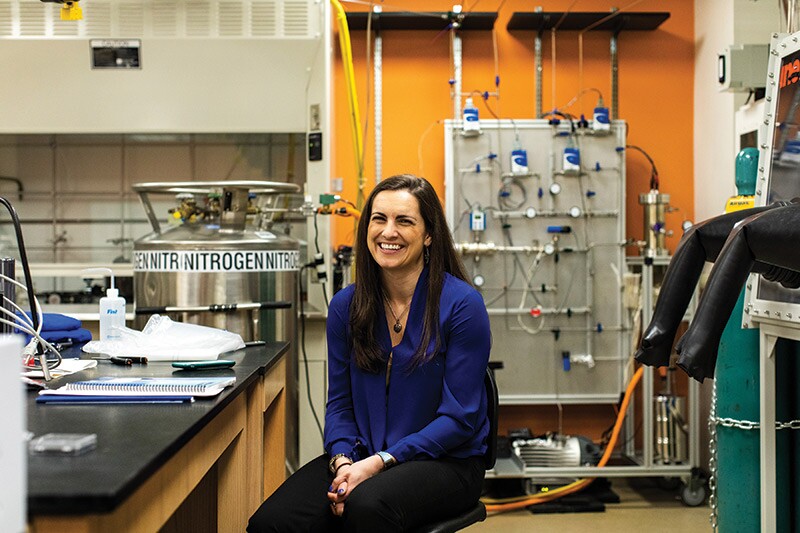

Walk into Sarah Hörst’s lab at Johns Hopkins University and you might find researchers simulating the haze surrounding exoplanets, experimentally recreating Titan’s atmosphere, digging through Hubble Space Telescope data for clues about Europa’s surface, or measuring wind speeds in Saturn’s atmosphere. The subjects of her work are every young scientist’s dream—exoplanets, planets, and planetary moons.

“It’s pretty common for kids to be into space, dinosaurs, and robots, and I guess I just never really grew out of that,” Hörst laughs. “My group is interested, big picture, in understanding the role that planetary atmospheres might play in the origin of life, or the evolution of life, those kinds of things. We do a lot of atmospheric chemistry and we use a number of different tools.”

As much as she loved space as a kid, Hörst never planned to pursue it as a career. “It’s funny because on my CV, it looks like I just decided I wanted to be a planetary scientist at 18 years old and that’s what I did. But that’s not what happened,” she says.

Hörst went to Caltech for college, intending to major in chemistry. When it was time to declare a major, she casually asked a classmate what she was planning to major in. When the classmate said planetary science, Hörst asked, “What is that?!” They talked and, as Hörst tells it, “I basically marched over to the registrar’s office and said, ‘I’m going to do planetary science.’”

Graduate school visits were another turning point. After double majoring in planetary science and literature, Hörst applied primarily to earth science graduate programs, planning to work on climate change—an area where she thought she could have a greater impact on the world. But when she visited earth science programs, things changed. “I knew [climate change] was important and I wanted to make a contribution, but I just wasn’t as scientifically interested as I was in planetary science,” she says. She had applied to a few planetary science programs as a backup plan and chose one of those instead.

Over the years Hörst has thought a lot about how the atmospheric and planetary sciences fit in with her drive to contribute to the greater good. She’s realized that all fundamental research has merit, even if it doesn’t seem immediately useful—that the value of increasing human knowledge has been proven over and over again.

In addition, she’s found planetary science to be a great way to spark kids’ interest in STEM. As a postdoc, Hörst revived a program in the American Astronomical Society’s Division of Planetary Sciences that helps K–12 teachers harness this excitement among their students when teaching math, reading, and other skills. Hörst has stayed involved in the program throughout her career, working to make it sustainable and even more useful to teachers.

The other thing she’s realized is that it’s really important for a person to be happy. Hörst notes that society often tries to devalue happiness—to make it seem like if you’re happy, you haven’t sacrificed enough of yourself for the greater good. In contrast, she believes that personal happiness contributes to the greater good. “Choosing a career in which you are happy has a positive impact on humankind in general,” she says.

Reflecting on her own internal conflict between a career in climate change or planetary science, Hörst advises students to “find a life that makes you happy.” She continues, “There are so many outside pressures trying to convince us to prioritize certain things or make certain choices. But at the end of the day, the person who has to live with those decisions is you. Figuring out what you need and want from life is one of the most important things that you can do.”

Sarah M. Hörst sits in front of the planetary atmospheric simulation chamber in her lab. Photo by Justin Tsucalas, Plaid Photo.